Great readers follow its news with particular attention, collectors covet each new edition and authors secretly dream of having their own. A look back at the very French publishing adventure of La Pléiade.

By Timothé Guillotin

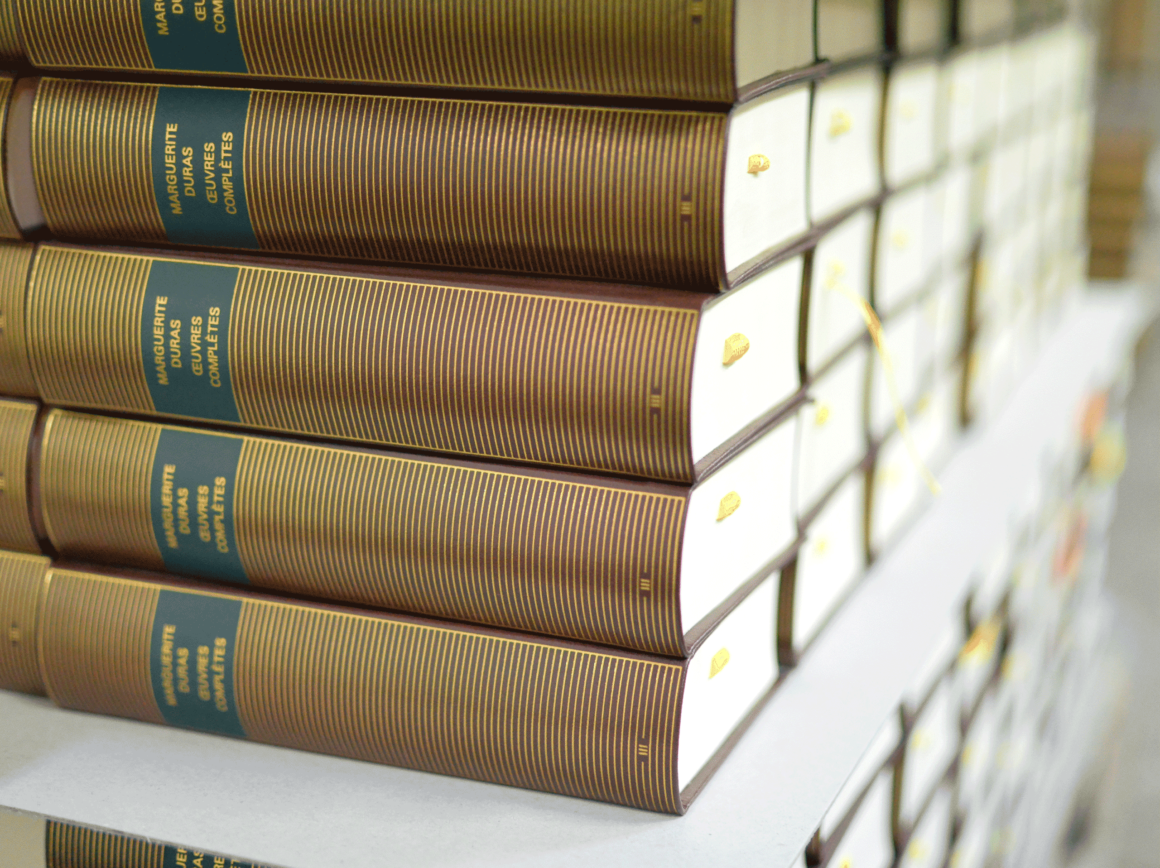

The look, already. Singular and prestigious. Just by its shape, the Pleiades evokes many values. It must be said that the manufacturing of the works, carried out in the Babouot workshops, north-east of Paris, leaves nothing to chance. Printed in the province, the text blocks are cut, assembled in booklets, sewn and then dressed in this iconic full leather cover gilded with fine gold. Upstream, it is colored according to a code adapted to the century of the work. Before being slipped into its case, each copy is covered with a transparent rhodoïd film that Gjyslaine, 42 years of house, urges to keep. Over time, the machines gradually began to accompany the team of expertly dexterous technicians, without detracting from their know-how or from the authenticity of the place. The Ile-de-France workshop is at the heart of the creation of La Pléiade books, which hold a unique place in the publishing landscape.

It all began at the dawn of the 1920s, when Jacques Schiffrin created the Pléiade editions. At the beginning, the house published Russian authors but, quickly, the publisher imagined an innovative collection: small books, inspired by the paperback, printed on bible paper and dressed with a prestigious leather cover gilded with fine gold. If form matters, it is because these amazing books are meant to house the complete works of eminent classical authors. And to allow readers “to have all of Racine in their pocket”, according to one of the collection’s advertising slogans. All the same! The first edition, composed of texts by Charles Baudelaire, was published in October 1931. This choice seems daring, but the risk is already part of the DNA of the collection. “Each publication is a gamble,” says Hugues Pradier, director of the Pléiade. This one turned out to be a winner.

The writer André Gide, who was close to Schiffrin, quickly took a liking to the collection. When the publishing house experienced financial difficulties, he quickly convinced his friend Gaston Gallimard to integrate the collection into his own house. In 1933, the deal was struck: the Pléiade became Gallimard, and Schiffrin remained its director. As for Gide, he became the first author to join the collection during his lifetime. In 1953, the Pléiade became part of the French cultural heritage with the publication of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s novels. The volume of seven books was a huge success: even today, the author of The Little Prince remains the best-selling author in the collection, ahead of Camus and Proust. Once the public has been won over, the editorial teams develop the famous critical apparatus. This work, often entrusted to a researcher, helps to make it a reference in the academic world. With the 1960’s came the time of opening up to other bodies of texts such as philosophy, religious writings and foreign authors. The first of them was Ernest Hemingway, in 1966.

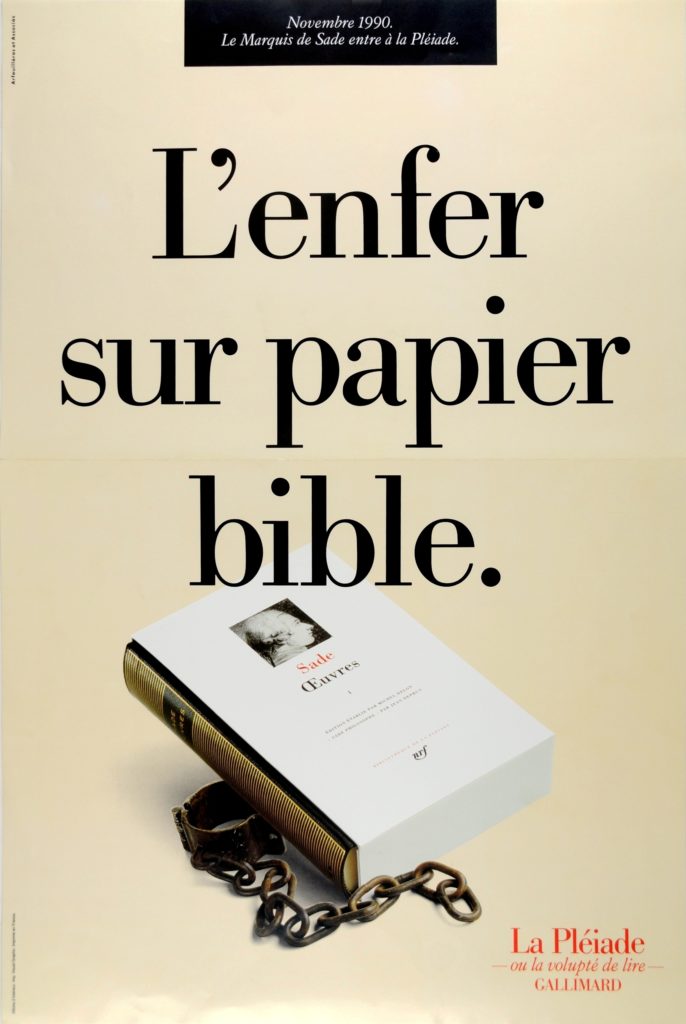

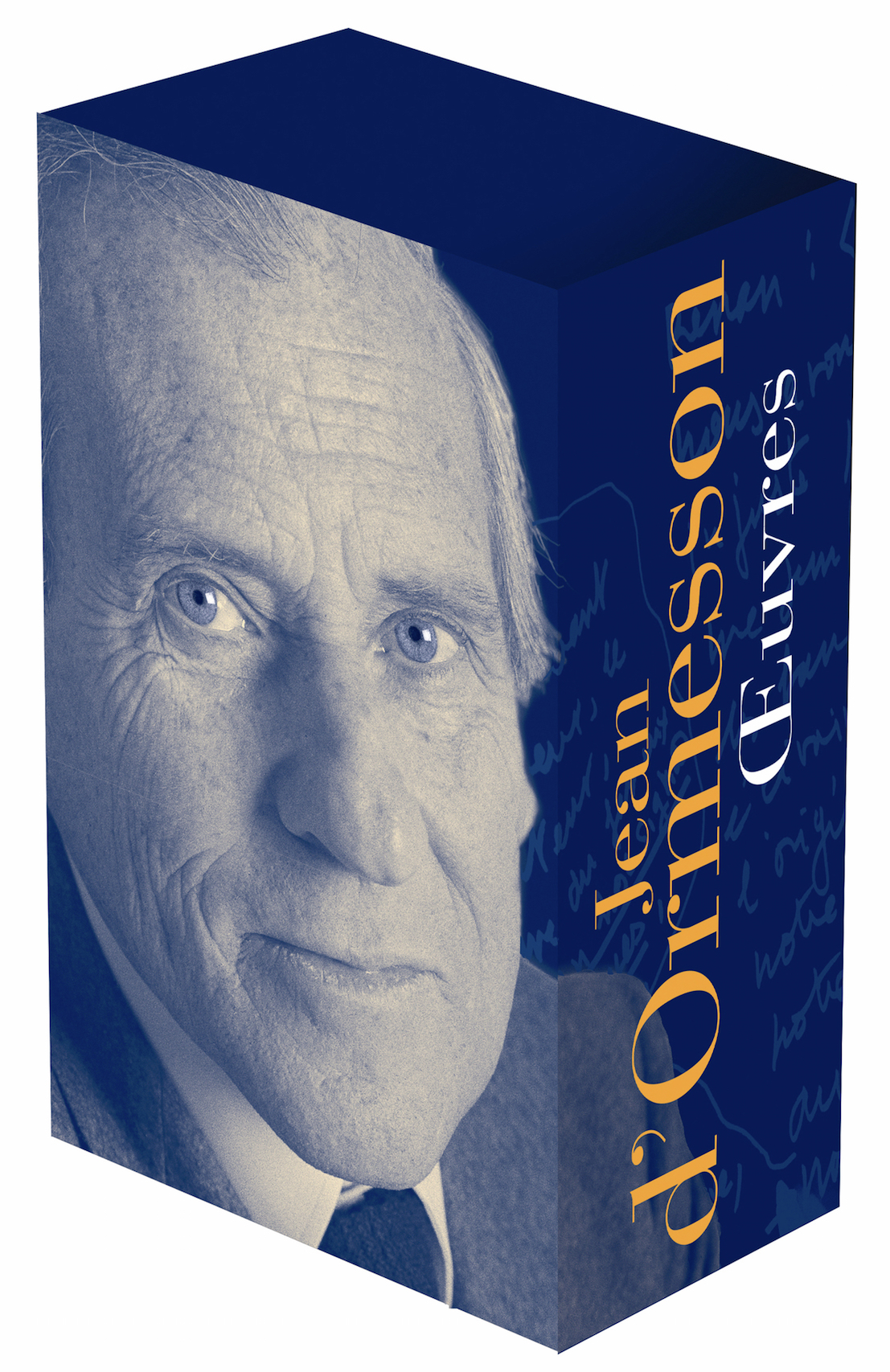

The popularity of the Pléiade can also be measured through the quarrels and polemics that its news provoke. Every new entrant brings with it its own set of debates. So it was with Jean d’Ormesson, two years ago. Immediately, some shouted imposture, others literary lobbying. The same goes for the Marquis de Sade, whose works were published in the 90s and caused a lot of ink to flow. Non-publications, too, create tension. There are many reasons for this, some of which are beyond the publisher’s control. This is the case of the texts of the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, which the Pléiade wants to publish but before being blocked in its project by a matter of rights. Generally, initiatives come from the editorial team of the house, from the management or from an academic. But sometimes a more surprising actor gets involved: the main character of one of Michel Houellebecq’s latest novels, for example, protests against the absence of Joris-Karl Huysmans in the collection. Gallimard’s staff is not insensitive to this as an edition dedicated to the writer is currently being prepared.

Près d’un siècle après sa création, la Pléiade est devenue un véritable agent d’influence dans le monde de l’édition. The sales figures speak for themselves: an author’s entry into the collection not only generates interest in his or her texts, but also leads to a considerable increase in the sales of other works. This double interest of economy and notoriety explains the obsession of some writers to want to be included. Like Louis-Ferdinand Céline, who, afraid of dying before he had his Pleiade, asked his publisher every week for his consecration. “Not in twenty years, but right now,” he insisted.