Former Soviet republic, neglected when it does not have a bad reputation, Belarus lingers in its past, but not only Soviet, offering, among others, the unusual opportunity to sleep in real castles.

By Dominique de la Tour

A modern airport, with clear halls, an affable policewoman: we don’t have this image of Belarus. Besides, does Belarus have an image? Who would mention Minsk as a capital city? Chagall born in Vitebsk? De Gaulle prisoner in 1916, in Shchuchin, in the west? A jovial guy hands me my 4X4. From the parking, I am surrounded by the average Belarusian landscape: the forest. Half of the territory is covered with pines, birches, mosses with the scent of russula.

And what about her? Do we know that she is here? The proverbial Berezina – the “River of the Birches” – lazes 40 km from the airstrip. I jump in. The GPS is blurred but my map is good: between the flaking shacks of Borissov and the trucks belching their black moods, I find the access to the swamps. Water hens trill. An old boat jingles its chain. Opposite, on the reed bank, a heron gobbles up a wriggling perch. Two bilingual steles: it is here that in 1812, by -40 degrees, the Dutch sappers of the general Eblé planted in the mire their bridges of pilotis. They will die frozen, in their entirety, but allowing the encircled Grand Army to escape by the other bank, in the disappointed growl of the Russian cannonballs. A local ran up with his worm-eaten box, where regimental buttons, equipment buckles, bullets and shoe studs were dancing. “Frantsouz ?” He offers me these relics, under the eye of a wife who, behind her dirty tile, makes sure that he does not make any discount…

On the road to Minsk, the giant 39-meter steel bayonet can be seen from afar: it is the mound of Slavy Kurgan, “Mound of Glory”, which celebrates the terrible tribute paid by the Belarusians against Hitler. But at the foot of the monument, the kids don’t care about this “Great Patriotic War” recounted in books: they play hanging on the barrel of a T34 tank, parked here in memory.

I reach the wide perspectives of the most “sovietostalgic” capital of Europe. Overlooking the lazy meanders of the Svislotch River, its colonnaded palaces face each other, staked with statues of engineers and kolkhoz women, topped with red stars, stamped like a passport with sickles and hammers. The fall of communism has slipped by like the rubber of an old raincoat. There was just this sudden infatuation with the mass, its dark canticles, its rises of yellow wax and incense fogging the icons. By the dozen, all the churches were rebuilt as they were in the 18th century.

By the way, my first night will be at the Monastirsky. Without much linguistic effort, this name tells me that the hotel was once a monastery: tiled corridors, whitewashed walls, 1960s sofas in cells that became comfortable suites. The cuisine is tasty but rustic. The service is more pleasant than stylish: a Slavic version of Parador, which feels bound to a zest of austerity for the sake of the monks who were once confined there.

The heart of Minsk does not sulk for so little bars and “trendy” breweries where a blond youth dreams of Rome or London, but drops its mojito for a peasant round as soon as a musician with embroidered shirt pulls on the accordion.

heading west : lakes, hilly fields…

Leaving the two Stalinist ziggurats of the Minsk Gate, I head west. Lakes, hilly fields like the folds of a cape where hundreds of storks peck. The wooden houses are spaced out, yellow, green, blue, with their wooden enclosures greyed by the winter and the extreme summers. On a highway bridge, an unmistakable sign suggests a strange visit: Dzerjinskovo. This is the estate where Feliks Dzerzhinsky grew up, a Polish hobo who joined the Bolsheviks to found the ruthless Cheka – the ancestor of the KGB.

Shaved to 20 cm from the ground, the birthplace slumbers in the damp breath of pine and juniper. A matron opens the museum for me, piously commenting on the paintings, the family photos, the table where the cruel Feliks took tea. I thank politely. And I continue towards the west, through this country decidedly full of curiosities.

I plan to push on to Brest. Brest-Litovsk used to be called the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: in the huge brick fortress rotten by shells in 1941, the Bolsheviks signed the peace of 1917 with the Germans. The city center is cute with its pedestrian streets where a young crowd alternates between taverns and terraces. In the forest of Brest, perhaps I would see the last bisons of Europe, even if they show themselves especially in winter, when laziness pushes them towards feeders furnished by the man.

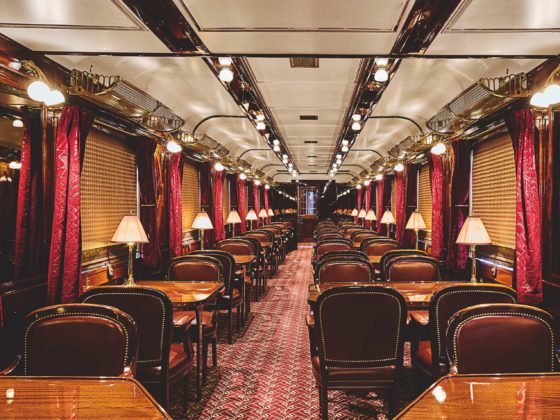

Tonight a unique hotel awaits me. Niasvij wraps itself in the emerald scarf of its moat where the mallards nasalate. The bastions protect a Renaissance palace. The pedimented entrance, an elegant porch with bulbous bell tower. I appreciate the vanishing lines of its fan-shaped courtyard, a real theater set where a Russian team is shooting a costume film.

A woman with a singing voice hands me the key. A marble staircase, corridors with secular flagstones give my steps a lordly echo. This huge door is my room. A long corridor and its bulging wardrobe as if I had ten francs and twenty clothes to put away. My bathtub takes its place in a tower, with a view on the ditches. I lie down on the bed. With a canopy, of course. On the wall, painted in oil, great lords and ladies look at me. Jérôme Bonaparte slept here, but it was Lithuanian princes who made the history of the place, the Radziwills. The restaurant has that simple and generous hunting lodge feel, serving refreshing khlodnik – a beet delicacy with apple vinegar and cream – or red caviar on potato pancakes – the sacrosanct draniki – because you can’t have a Belarusian meal without pancakes.

Niasvij will not be the only unreal place where I will sleep. Barely 30 km to the north laps this small lake, where twenty nuns in white throw pebbles, under the indulgent gaze of two abbots. A fortified castle highlights the marquetry of stone and brick of its five towers. A place of arms with a wrought iron well is surrounded by high steps and a labyrinth of gothic rooms. This is Mir’s castle and it is also a hotel.

It is late. The tourists have left, but the heavy oak door remains open. A guard with a flashlight is on sentry duty. I tell him that I want to go out to stroll along the pond. “But of course, lord: at night the castle is yours”. That’s how I feel: I wander through the floors with their leaded stained glass windows and illuminated coffers, then I go down to the cellar for dinner with its wide vaults and discreet waiters, with the impression of being the master of the house.