In the heart of Brive-la-Gaillarde, in Corrèze, the Denoix family distillery, born in 1839, perpetuates a historical know-how to elaborate exceptional liqueurs.

By Romain Rivière

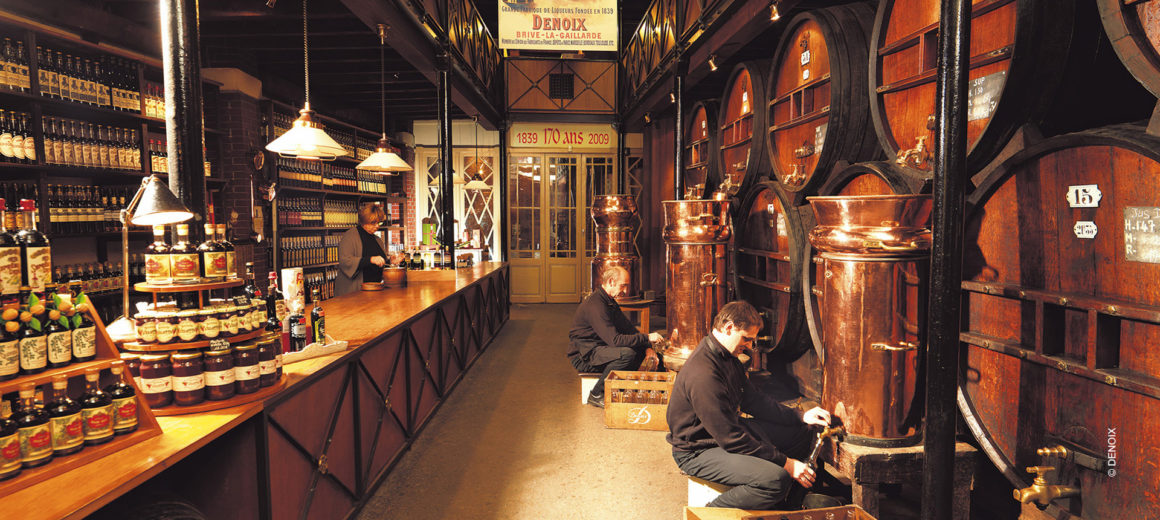

First, take a tour of the collegiate church of Saint Martin, the epicenter of the city. Then walk up the pedestrian streets to soak up its style and its preserved architecture, made of stone and slate, giving Brive-la-Gaillarde all its charm, up to the boulevard du maréchal Lyautey, three or four minutes walk from the building. It is here, in this historic building, that the Denoix distillery has been located since 1839, an inseparable part of the city of which it is one of the icons. In this emblematic place, it is above all a family history that has been written for 180 years. The recent arrival of Marie and Paul Bastier, respectively daughter and son-in-law of Sylvie Denoix-Vieillefosse and Laurent Vieillefosse, marks the transmission of this historic company – labeled Entreprise de Patrimoine Vivant (EPV) – to the fifth generation.

The first page of this history was written in 1839 by Pierre Lacoste, quickly joined by Louis Denoix. At that time, the region saw the birth of many distilleries, responding to the growing demand for aperitifs and, above all, for extra-fine liqueurs whose digestive qualities were then recognized. In Brive-la-Gaillarde, this “laughing gateway to the South” dear to the poet Jasmin, craftsmen work with love on cognac and armagnac, the two main brandies of the South West. The city is also marked by the wine influence of Bordeaux, but also of Cahors and Bergerac, where the ratafias and walnut wines are of great quality.

Pierre Lacoste and Louis Denoix, specialized in triple-dry curaçao, launched Suprême Denoix shortly after their installation, which is still the spearhead of the distillery’s range today. It is a tasty nut water, known for many of its virtues. “It is made with the July walnuts, full of juice when the shell and the kernel are not yet formed,” explains Denoix. The nuts are crushed, and the juice macerated in alcohol and aged for five years in oak barrels in order to bring the great aromatic complexity of the woody, as well as the flavors of vanilla, cocoa and coffee specific to this exceptional liqueur, finally assembled with armagnac, cognac and a sugar syrup cooked over a wood fire.

Over time, the distillery expanded its offer. In the middle of the 20th century, Elie Denoix started making violet mustard, which Bernard Denoix relaunched in the 1980s, giving it an international reputation that established the reputation of the Gaillarde company. History, this mustard, made with grape must and fine mustard seeds, owes its fame to Pope Clement VIwho was born in Corrèze and who, in the 14th century, remembering that an excellent violet mustard was made there, brought a mustard maker from Turenne – not far from Brive – to Avignon to make an identical product. The violet mustard becomes then a tradition of Brivé, until the XIXth century. Emblematic of French excellence, this mustard owes its survival to the attachment of Elie Denoix and his children and grandchildren.

To cross the threshold of the Denoix distillery is to plunge into an environment that has remained unchanged for 180 years, made of copper and oak, noble materials that have served and continue to serve the master liquorists of the house. Here hovers a fragrance of fruits and plants carried by the angels. In the morning, the fireplaces glow and the alembic lets the vapors escape, while the copper cauldron bubbles: the elixirs, as in the 19th century, are made manually. In the heart of the cellar, the old copper alembic with bain-marie of the Charentais type is enthroned on a coal-fired hearth. Allowing the liqueur maker to extract the aromas present in the fruits or plants in order to perfume the alcohol, this period still, which constitutes a true heritage of the house, remains at the heart of the elaboration of liqueurs.

“Thanks to this distillation, the concentration of aromas is optimal and allows a fine selection by discarding bad tastes”, they say at the distillery. First, the plants or fruits are macerated in a neutral or noble alcohol like armagnac. Then the vat is gently heated, and the alcohol vapors carry away the concentrated perfumes. “At the exit of the hood, the swan neck guides the vapors to the coil bathed in a water tank, and the distillate that condenses there can be collected at its exit,” we continue. The alcohol, rich in aromas, is then colorless and titrates at 80 degrees. The liquorist then works with all his know-how to isolate the heating core. “The most qualitative is kept for the elaboration of liqueurs”, assures the spokesman of the company.