It is off the coast of the Philippines that Jewelmer has been producing, since 1979, a rare hope of cultured pearls: the golden pearl of the South Seas. Reportage between Manila and Palawan.

By Romain Rivière

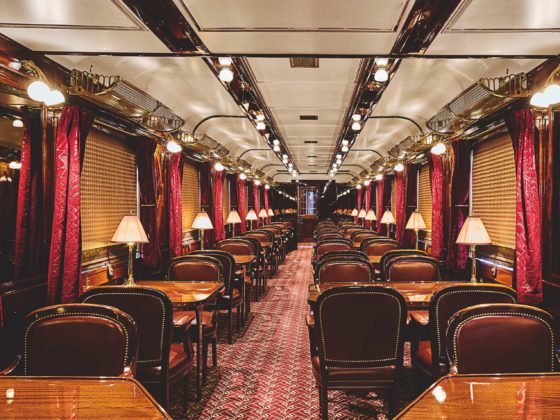

Just a little turbulence. Not enough to panic the ATR 42-500, which has been flying for an hour and a half from Manila, in the direction of the southwestern Philippines. The aircraft, whose ageing appearance struggles to hide its advanced age, has seen others: here, off the coast of the archipelago, the weather has its moods; the blue sky, in an instant, can give way to the most violent winds. In the end, only the landing at El Nido airport, in the north of Palawan island, was executed with some aggressiveness. It must be said that the runway is short, barely 700 meters, and that its orientation facing the sea, surrounded to the east by mountains, forces the pilots to operate the approach and the final in sight. After two bounces, the turboprop finally slows down, before coming to a halt in the process. A kind of sandy esplanade, where some weeds are fighting, is used as a tarmac. The bamboo terminal looks like a hut planted in the middle of a vast vegetation. To the west, the sea extends as far as the eye can see. In the east, the valleys of the long Palawan stretch from north to south for nearly 300 kilometers. Calmness reigns. The glitter of the Place Vendôme is far away. The contrast is striking. And it is here that the Jewelmer company was established in 1979.

Founded by former Breton airline pilot Jacques Branellec, who worked in Tahiti for many years before turning to pearl farming, Jewelmer produces a rare species: the golden South Sea pearl. Over the years and the water, and after ten years of research and reproduction trials of the Pinctada Maxima oyster, the only species able to produce pearls with golden mother-of-pearlThe company has built up an empire of 1,000 employees, capable of producing several hundred thousand pearls each year. Of this production, only a tiny part is dedicated to fine jewelry. Between 5,000 and 7,000 pearls: the roundest, the largest, the most golden, the most brilliant. These are booked many months in advance by the big houses, such as Cartier, Tiffany & Co or Hermès. And their prices sometimes exceed a hundred thousand euros. But each time, at the time of the harvest, it is the surprise. “From one year to the next, production varies. We never know what nature has in store for us,” explains Jaques-Christophe Branellec, the founder’s son and director of the company. It must be said that six to seven years of work are necessary to develop a pearl.

Everything happens on one of the pearl farms, installed on small islands of the archipelago. Terramar remains the most important of them. Surrounded by turquoise water, it is home to 250 employees, living in community and self-sufficiency. Most of their consumption – fruit, meat, fish – is produced locally; only a few thousand tons of fuel are delivered each year to run the few electrical installations and, above all, the indispensable boats and helicopters remain the only means of reaching the farms. There, live biologists, divers or security agents, ensuring the smooth running and discretion of operations, whose procedures are kept secret.

The complexity of the culture is based on the quality of the oysters. To select the best elements, the biologists control daily, within their laboratory, the mollusks whose reproduction they manage. Feeding, water temperature: every detail counts, in order to obtain oysters with golden lips likely to produce perfect pearls. This development work requires five years of work. Then comes the stage of pearl culture, which begins with the grafting of the nucleus, preceding two to three years of underwater development. But the matter is not simple: 400 steps make up the process of developing the pearl, each one influencing the next, making the result quite uncertain. One of the difficulties lies in the cultivation carried out in the open sea, in open waters. Plankton quality, water temperature or current violence can thus modify the quality of the pearl. A lack of protein, for example, can make it lighter. So when the time for extraction comes, the pressure mounts. “This stage, the last one, is moving. For the biologist, the moment is similar to that experienced by the surgeon seeing his patient again a few years after an operation,” says Jacques-Christophe Branellec.

To optimize its chances of success, the company relies on the involvement of its employees and management based on trust. And the result is there, since in the families of farmers, the generations follow one another.